The Thai Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU) 1954 – 1974

For the special operations insignia collector, Thailand’s myriad of airborne and special warfare units presents a seemingly endless variety of badges to collect. A trip to the military and police regalia suppliers clustered around the Thithong Road area in Bangkok can be overwhelming as each shop appears to offer their own unique variations of the official parachutist wing patterns. It will be an impossible task to try to collect all the Thai jump-wing insignia and I gave up many years ago as I began to narrow my focus to specific conflicts or units.

I am still chasing some of the older Thai wings, including the rarely found first pattern Army wing that was awarded in the 1950’s and early 60’s, but it remains a ‘holy grail’ insignia for me and is rarely seen in the marketplace.

.

The Police Aerial Resupply Unit (PARU) of the Royal Thai Police is the one Thai unit that still remains within my collecting focus, although I do restrict myself to insignia from its formation up until 1974. Its innocuous sounding name was a deliberate act to disguise the role and function of this elite special operations unit that was in fact sponsored by the CIA and was one of the first clandestine groups deployed into Laos, way back in 1960.

After Mao’s victory in China in 1949, the USA became increasingly concerned about the spread of communism in South East Asia. In response to fears that the Chinese could invade Thailand, the CIA set up a station in Bangkok and in August 1950 arranged to train selected members of the Royal Thai Police, who were seen as more reliable than the army, in counter-insurgency tactics.

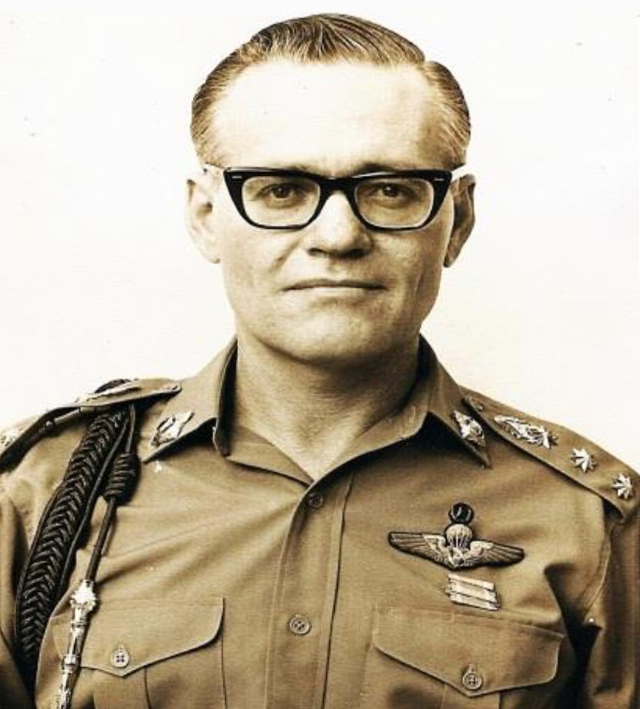

In March 1951, James William “Bill” Lair, a CIA paramilitary officer arrived in Thailand for this, his first assignment. With the assistance of the Agency’s front organisation, Southeast Asia Supply Company (SEA Supply) which would later be operating out of an office on the infamous Patpong Road, Lair identified an old Japanese camp at Lopburi to be used as the training camp. The course was designed to run for 8 weeks and included unconventional warfare and parachute training. The initial cadre of 50 volunteers came from the police but later recruits came from all branches of the Thai military as well as the police. The graduating groups were initially called the Territorial Defense Police, but these later became known as the Border Patrol Police (BPP).

As the threat of Chinese communist invasion subsided the program was threatened with cancellation which concerned Lair as the ‘knowledge base’ which had been developed would be diluted if the units were broken up and the men dispersed across the country. Pressure was also being exerted to turn the base, named Camp Erawan, at Lopburi over to the Royal Thai Army. In response Lair managed to convince the US Embassy and the Director-General of the Thai National Police Department, General Phao Siyanon to turn the force into an elite special operations unit. General Phao eagerly accepted the proposal as it would provide him with a militarised force that could counter the other two strongmen in the Government at that time, Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram and General Sarit Thanarat. Phao’s only condition was that Lair be a serving Police officer and after permission was granted by the US Government, Lair was appointed a Captain in the Royal Thai Police.

Lair then selected 100 personnel from the previous 2000 course graduates to undertake advanced instruction at their new base, next to King Bhumibol’s Summer Palace at Hua Hin on the coast. This was then followed by a further 8 months of training including offensive, defensive and cross-border operations, before some of these volunteers in turn became the cadre responsible for training new recruits. On 27 April 1954, King Bhumibol attended the official opening ceremony of their base, Khai Naresuan at Hua Hin and that date subsequently became recognised as the unit birthday.

By 1957, the unit which consisted of two rifle companies and a pathfinder company, commanded by Captain Lair himself, was called the Airborne Royal Guard. However, in September of that year a coup was mounted by Army General Sarit Thanarat and Police General Phao was sent into exile. Lair’s unit which was seen as being loyal to Phao faced being disbanded but managed to survive due to perceived support from the King and in early 1958 was rebranded as the Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU). The intention was to eventually integrate the PARU into the Royal Thai Army and their headquarters was moved to Phitsamulok in Northern Thailand, although they still maintained their Hua Hin base, Camp Naresuan, as well.

It was also at this time that the unit became more closely involved with the CIA’s international operations, rigging parachutes for weapons drops to insurgents in Indonesia, and pallets of weapons for delivery to the anti-Chinese resistance in Tibet. Then, early in 1960, PARU’s pathfinder company was sent to the Thai-Lao border to gather intelligence from the ethnic minority groups straddling the border region.

.

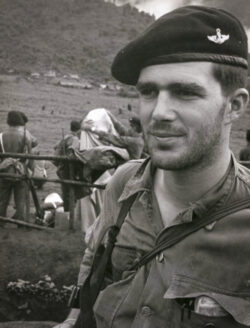

In August 1960, Laotian paratroop officer, Kong Le led his unit on a coup which overthrew the Royal Lao Government. Many of Lair’s PARU troops were Thai citizens, but of Lao origin and could seamlessly blend into the Lao population, so permission was given for Lair and five teams of PARU to join the ousted Lao head of state (and General Sarit’s first cousin), Phoumi Nosavan, to prepare for a counter coup. The five man PARU teams spread throughout Phoumi’s forces providing a radio network able to communicate with Lair who was headquartered in Savannakhet and these were instrumental in the successful counter-coup of 14 December 1960. Lair then moved to Vientiene and the PARU’s long involvement in the ‘Secret War’ in Laos followed.

.

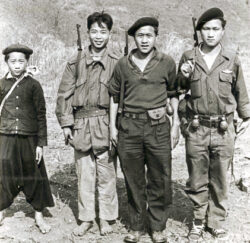

In January 1961, Bill Lair made contact with Hmong hill-tribe commander, Lt. Col. Vang Pao and three groups of five PARU commandos were inserted around the Plain of Jars to train his forces. By the middle of the year of the 550 strong PARU unit, 99 of its commandos were operating in northern Laos and Hmong special operations teams were being trained by the PARU back in Hua Hin. Funding for this was provided by the Programs Evaluation Office of the CIA under the code name Operation Momentum and eventually resulted in a clandestine army of 30,000 Hmong under Vang Pao’s command which included the battalion sized Hmong Special Guerrilla Unit and also a 30 man cadre from the Laotian paramilitary Directorate of National Co-ordination (DNC).

In 1963 the PARU was coming under pressure from the army controlled government who had allowed the unit to continue to exist on the premise that it would be integrated into the Royal Thai Army. A joint Police-Army Special Battalion was to be stationed at the PARU camp in Phitsanulok, with the commander being Army Special Forces and two deputy commanders, one from PARU and one from Army Special Forces. The intention was to eventually integrate the entire PARU into the battalion, but the PARU resisted integration and kept the bulk of its manpower at Hua Hin.

In 1964 it began training Cambodian and Laotian troops in commando and guerrilla warfare techniques at Hua Hin. The PARU also remained active in Laos and its training mission was expanding both in Thailand and also in northern Laos. It was also conducting reconnaissance and raiding operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Inevitably, the tempo of operations began to take its toll on the unit and towards the end of the decade, a retraining programme needed to be implemented to rebuild the unit into a 700 man battalion composed of ten detachments. In addition, by 1969, the unit had developed air and sea rescue sections as part of its role. The former providing a capability similar to that of the USAF Pararescue, locating and picking up downed aircrew within Laos.

By the early 1970’s Thailand’s attention had begun to shift to the threat posed by the Khmer Rouge insurgency on the Cambodian border and PARU teams conducted several reconnaissance missions into the Khmer Republic. In 1973, thirteen years after first deploying to Laos the last PARU teams departed that nation. Then as Thailand started to grapple with its own communist insurgency it began conducting operations with the Border Patrol Police to combat insurgents in the south of the country, an area where it is still active today. Since 1974 much has changed for the PARU, including the establishment of the Royal Thai Police Special Operations Unit “Naraesuan 261” under its auspices in 1983. This specialist counter terrorist unit has been involved in several hostage release operations since its formation and is also responsible for providing specialist executive protection teams for the Thai Royal family and visiting dignitaries. However, as my focus is related to the PARU’s activities up until the mid-1970’s I will save the post-1974 years for a future article.

One Comment

Comments are closed.