The funeral of General Trình Minh Thế and the Cao Đài badge debate

On 3 May 1955, while standing near his military jeep, Vietnamese army Brigadier-General Trình Minh Thế was killed by a sniper’s bullet. Thế was an ultra-nationalist Caodaist commander who had in turn fought the French and the Viet Minh before integrating his Cao Đài Liên Minh militia into the Vietnamese National Army of the Ngô Đình Diệm administration. Diệm, who had been struggling to maintain control against the demands of the three major sects, the Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo and the Bình Xuyên, immediately set out to enshrine General Thế as a national hero who gave his life in defence of the government, rather than be swayed by sectarian interests.

General Thế was buried with full military honours and the ceremonial procession of his casket being solemnly paraded through Saigon was photographed by LIFE photographer Harrison Forman. I believe that Forman’s photographs played a significant part in the ongoing mis-identification of the Vietnamese Army general service hat badge as being a ‘Cao Đài badge’.

In June 1954, Ngô Đình Diệm had returned from exile to establish a new government in the South of Vietnam. He faced an uphill battle as he lacked control of the military and police forces and the civil system was still administered by French officials. He also encountered opposition from the French expatriate community who wanted to maintain France’s interests in South Vietnam and, not insignificantly, from the three major sects, the Cao Đài, the Hòa Hảo, who both fielded large sectarian armies, plus the Bình Xuyên an organised crime syndicate that controlled the National Police force. When Diệm returned to Vietnam in 1954 these three groups controlled approximately one third of South Vietnam and it was not until the Battle of Saigon in April 1955 when the Bình Xuyên were crushed that he was able to consolidate his grip on power.

Staunchly Catholic, Ngô Đình Diệm detested these groups. The Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo, he claimed, were born from the Communist Party of Indochina but without a strong reliable military force of his own he initially had to play a pragmatic game of political cat & mouse with them. When, on 20 January 1955 the French agreed to turn over the full control of the Vietnamese armed forces to the Vietnamese government within five months, Diệm was placed in a slightly better position. The transfer would see the end of the regular French pay for the Forces Suppletifs which included the sects private armies and American financial backing of the Diệm gave him the leverage he needed.

Caodaist, Trình Minh Thế was the first to shift allegiance to the new paymaster and after receiving a substantial (American financed) bribe from the government along with the rank of Brigadier-General, he marched his Lien Minh force into Saigon on 13 February 1955 for integration into the Vietnamese National Army.

Later, when the “United Front of Nationalist Forces”, a coalition of the sects sent an ultimatum to Diệm to form a government of national union, Trình Minh Thế threw his support behind the Front, but then, after another substantial bribe, switched back to Diệm. The dispute between the Front and Diệm’s regime finally reached tipping point at the end of March 1955 and resulted in the brief civil war, culminating in the Battle of Saigon that gave Diệm the victory he needed.

General Thế, who was hated by the French, but seen by the Americans as a possible replacement for Diệm due to his recent anti-communist stance was assassinated by a sniper’s bullet to the back of his head on 3 May 1955. The murder was unsolved, with some blaming the French who had vowed to kill Thế due to his implication in a series of bombings between 1951-53. The French also suspected that he was the mastermind behind the Caodaist suicide bomber assassination of French General Chanson, the Commander of the French-Indo-Chinese forces in South Viet Nam in 1951. Others suspected that Thế’s murder was orchestrated by the Diệm administration who saw him as a threat to their power and possible replacement to Diệm.

The truth remains unknown, but Ngô Đình Diệm immediately set out to enshrine Thế as the first national hero of his independent non-communist South Vietnam. He was praised by the press for his ‘genuine patriotism and heroism’ which was juxtaposed with the treachery of the dissident Hòa Hảo and Bình Xuyên leaders. According to author, Jessica Chapman in her book Cauldron of Resistance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and 1950s Southern Vietnam, the Vietnamese newspaper obituary described his support for the Diệm regime was “because he realised the forces of the national army were struggling for the country”. In fact, Trình Minh Thế’s decision was due to the substantial bribes channeled through CIA agent, Edward Lansdale.

This inconvenient truth was ignored by the government, who pushed hard to ensure that he was seen as a hero, giving his life in the defence of Ngô Đình Diệm’s administration. On May 4th and 5th the state gave Thế an official funeral including a military procession from his home to a temporary resting place in front of the Saigon Town Hall where four Vietnamese National Army officers stood watch over his body day and night.

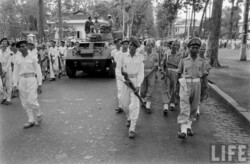

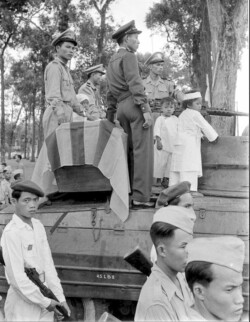

The funeral procession saw his casket, draped with a black banner with silver lettering proclaiming, “State funeral of General Trình Minh Thế, national hero” transferred on an armoured car accompanied by an honour guard of his former Cao Đài Liên Minh troops who were by then, regular soldiers serving in the Vietnamese National Army.

It was during this procession that LIFE photographer Harrison Forman took his famous photographs which show soldiers wearing both the later ‘unification of the sects’ variation Cao Đài pocket insignia AND the general service beret badge of the Vietnamese National Army. I believe that it is largely due to these photographs that the beret badge was erroneously attributed as an exclusively Cao Đài insignia in the reference books that appeared from the 1970’s onward. Some, such as the 1986 French Symboles et Traditions (S&T) reference book Les Insignes de l’Armée Viet Namienne described the badge with some reservation (translated) as “Without any confirmation, this badge could be the beret badge of the Cao Dai army”.

Other insignia references have been less cautious in their descriptions and the ‘Cao Đài badge’ myth has subsequently been repeated in several books but without ever identifying the evidential source. I suspect that many may simply be repeating the information contained in other existing references and have not taken into account the mass of evidence that is now available.

There is a lengthy debate surrounding the badge on the WAF forum where the ‘Cao Đài badge’ theory was placed under the spotlight. It is worth reading as it provides insightful discussion and a compelling argument against this being an exclusively Cao Đài insignia. Evidence such as the 1958 insignia reference board compiled and labelled by the US Defense Attache’s office in Saigon (see below) have emerged from collections and been invaluable in helping further knowledge about the subject. The debate about this Vietnamese Army general service badge has been settled, but I suspect that Harrison Forman’s funeral photographs may have played a large part in the earlier incorrect attribution of the insignia.