The French Foreign Legion Museum – Myth, Legend and History

We can certainly risk a few Legionnaires for France. After all, they are mostly foreigners. Minister to François Marneau in the 1977 film March or Die

The French Foreign Legion, founded in 1831 by King Louis-Philippe, is a unique military unit composed of volunteers from around the world, often drawn by the promise of adventure or a second chance. Renowned for its fierce discipline, demanding training, and unwavering loyalty, the Legion has fought in nearly every major French conflict, from Mexico, Algeria and Indochina to more recent operations in Africa and the Middle East. Its mythology is built on the ideals of honour, brotherhood, and sacrifice, with a code that places the Legion above individual origins. Cloaked in legend and romanticism, the Legion is often seen as a symbol of redemption through service and a testament to the enduring spirit of those willing to fight and die for France.

Nestled in the Provençal town of Aubagne, just north of Marseilles, the French Foreign Legion Museum presents a tribute to this tradition. It serves as both a cultural institution and a memorial, with exhibits spanning nearly two centuries of military campaigns, showcasing artifacts, personal effects, uniforms, and weaponry.

Musée de la Légion étrangère Exhibits

The Legion Myth and Origins, From Algeria to Mexico

Upon entering, visitors move into an introductory area dedicated to the Legion’s cultural legacy: its depiction in films, literature, songs, and visual arts.

From there, visitors progress through a thematic and chronological route through the Legion’s military history. The journey starts in Room 2 with the Legion’s formation in 1831 by King Louis Philippe, progressing to the formation of the 1st Foreign Regiment (1er RE) in Algeria in 1842 and the campaigns in Crimea and Mexico.

Far Horizons: Colonial Expansion

Room 3 covers France’s colonial expansion in the late 19th century, including the Legion’s role in the establishment of what would become French Indochina. This room also documents the fighting in Dahomey and Sudan in the 1890s along with the expedition to Madagascar in 1895. It concludes with the early 20th century campaigns in south Oran and the establishment of Morocco as a French protectorate in 1912.

World War 1 and the Interwar Period

The next section, Room 4, explores the Legion experience during the First World War and the inter-war period when the Legion was engaged in fighting in Lebanon and attempting to pacify the ongoing resistance in Morocco.

In 1919, following the First World War, the Legion returned to North Africa and Sidi-Bel-Abbes became the headquarters of the Foreign Legion. It was soon engaged in operations in Morocco, leading to the French engagement in the Rif War (1925 – 26) and eventually, ‘pacification’ after the fighting at Djebel Saghro in 1933. For many, thanks to Hollywood and numerous books, this is the most well known and ‘romantic’ period of the Legion, although the reality was anything but that.

World War II

Room 5 documents the role that the Legion played during the 2nd World War, where following the Armistice of June 1940, some regiments are dissolved and legionnaires are sent back to North Africa. Around the same time, the 13th Half Brigade form the nucleus of the Free French Forces, distinguishing itself between 26 May and 11 June 1942 in the Battle of Bir Hakeim.

Indochina and Algeria

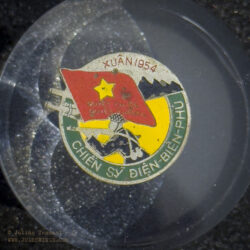

Following World War 2, the Legion was heavily involved in the Indochina War, trying to hold on to France’s colonial possessions in South East Asia. Never popular at home, the war in Indochina was fought by colonial troops and volunteers including a significant number of Legionnaires. It culminated in the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in May 1954. Around 70 000 Legionnaires fought in Indochina with 12 000 being killed and the campaign is the bloodiest in the history of the French Foreign Legion.

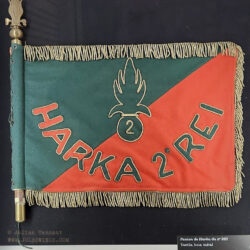

Then, on the 1st of November, 1954, the massacre of civilians by the separatist National Liberation Front marked the beginning of the Algerian War. By 1958 the French are militarily dominant but isolated politically. French President, General de Gaulle chooses to allow Algerian self-determination, prompting a backlash from elements within the French population in Algeria. This is supported by elements of the Army, including officers of the famous 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1 REP) and the 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment (1 REC). In April 1961, the dissenters launched a failed coup attempt, which results in 1 REP being disbanded and the CO of 1 REC being imprisoned.

‘Je ne regrette rien’ being sung by the officers of the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment, whilst being detained at Fort Nogent between May and June 1961. This song is an adaptation of the famous song by Edith Piaf (see end of post) with the lyrics changed to reflect their situation.

Room 6 is devoted to both French Indochina and the Algerian Campaign, but considering how important these conflicts are in the history of French Foreign Legion, the number of artifacts on display is minuscule. This was my biggest disappointment in the museum.

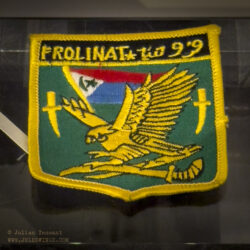

50 Years of External Operations

The next area, Room 7, is devoted to the activities of the Legion after departing Algeria. This includes operations in Africa such as the famous Dragon Rouge, operation in Kolwezi conducted with the Belgian Paras, peace keeping operations, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan amongst others. Once again, a lot of history compacted into a very small exhibition space.

The Builder Legionnaire

Room 8 is called ‘The Builder Legionnaire’ and is devoted to the engineers, pioneers and sappers of the Legion. This is a relatively large room with less material on display and some of the space could possibly have been better utilised expanding the exhibits from the previous rooms.

A Legionnaire’s life and Solidarity, the Museum Story

Room 9 covers the Legionnaire’s life and the activities of the Foreign Legion band which is followed by displays in Room 10 relating to Legion solidarity, the legion ‘family’ and the life of the museum.

The Honour Room and Crypt

Visitors then proceed to ‘The Honour Room’ which pays tribute to the traditions and values of the Legion. This area which resembles a formal dining room is where new Legionnaires receive their contract after completing their training and where they receive their discharge prior to returning to civilian life.

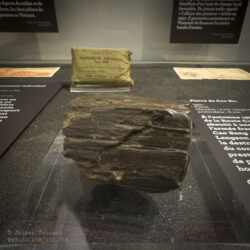

The final section is ‘The Crypt’, hallowed ground where the articulated hand of Captain Danjou, along with the dirt and bones of Lieutenant Maudet and the Legionnaires killed at Camerone are surrounded by walls inscribed with the names of officers killed in combat and the flags of the Foreign Legion Regiments.

The hand is believed to have been taken from the battlefield as a souvenir by a Mexican soldier and who later passed it to a French ranch owner known as L’Anglais, in the state of Puebla. In July 1865, more than two years after the battle, L’Anglais sold the hand to an observant Austrian officer, Lieutenant Gruber, who delivered it to the French high command. It was then finally returned to the Foreign Legion.

It is preserved under glass in a climate-controlled, secure reliquary in the museum’s crypt and brought out only once a year, on 30 April, during the commemoration of the Battle of Camarón, the most important date in the Legion’s calendar.

Exit through the Gift Shop

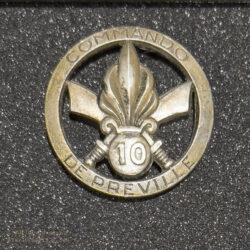

Visitors then proceed back to the entry via the museum’s extensive gift shop, which is actually larger than some of the exhibition rooms. Playing to the mythology, the shop sells a range of Legion related memorabilia including books, clothing, alcohol and copies of the insignia used by the Legion units.

Reflections

Overall, the French Foreign Legion Museum is well organized and offers visitors a chronological journey through the history of the French Foreign Legion. However, it presents a highly curated narrative that leans heavily into the myths and romanticism long associated with the Legion, while glossing over many of the more controversial or difficult aspects of its past. Certain episodes are emphasized disproportionately, while others—particularly more recent operational history—are given little to no attention. For collectors or visitors interested in post-1945 artifacts and equipment, the museum is likely to disappoint, as this period is notably underrepresented.

For those seeking a more comprehensive and tangible exploration of the Legion’s material history, especially its uniforms and field equipment, a visit to the museum’s Uniform Annex is essential. Located at the Legion’s Institution for Disabled Veterans (Institution des Invalides de la Légion Étrangère, IILE) in Puyloubier, about a 45-minute drive or 2.5 hours by public transport from Aubagne. The annex houses five rooms with over 100 mannequins dressed in original uniforms. This collection spans from the Legion’s founding in 1831 through to 1962, when the Legion relocated its headquarters from Algeria to mainland France.

Unfortunately, due to the distance and timing considerations when using public transport, I was unable to get to Puyloubier to see this collection during this trip. However it is definitely on my list of places to visit next time.

Visitor Information

Musée de la Légion Etrangère

Chem. de la Thuilière 1

3400 Aubagne

France

Contact

Phone: +33 4 4218 1096

Website: https://www.legion-etrangere.com/

Email: musee.legionetrangere@gmail.com

Opening times

Tuesday to Sunday 10:00 – 12:00 / 14:00 – 18:00

More Military Museum Reviews Here

“Non, je ne regrette rien”, meaning “No, I regret nothing”, is a French song composed by Charles Dumont with lyrics by Michel Vaucaire. Written in 1956, it became famous through Édith Piaf’s iconic 1960 recording. Piaf dedicated the song to the French Foreign Legion.

At the time, France was embroiled in the Algerian War (1954–1962), and the song was adopted by the Legion after the failure of the 1961 putsch by elements of its leadership. Following the attempted coup, the senior officers involved were arrested and tried, while the non-commissioned officers, corporals, and Legionnaires were reassigned to other Legion units.

As they marched out of their barracks, they sang “Non, je ne regrette rien”—a moment that cemented the song as part of the Legion’s heritage. It is still sung during parades today.