Musée des Parachutistes. The French Paratrooper Museum

Since their operational debut in World War II, French airborne forces (troupes aéroportées) have played pivotal roles in both national defence and France’s overseas interventions. The Musée Mémorial des Parachutistes (also known as the Musée des Parachutistes) is located within the grounds of the French Parachute Training School (ETAP) in Pau and is dedicated to the legacy of these elite units.

Museum Structure and Layout

The museum is organized into five permanent chronological exhibition spaces, each illustrating a distinct phase in the history of French airborne operations. These sections are introduced by audio-visual displays which give context to artifacts being displayed.

Zone 1. Origins and World War II

This section explores the foundational doctrines of airborne warfare, the formation of France’s first paratrooper units, and their deployment during WWII. Particular attention is also paid to the influence of Soviet and German developments in the interwar period.

This section of the museum then moves on to document the Free French airborne and special forces units that fought to liberate France during World War II. At the outbreak of the the war, both the 601e and 602e GIA had been moved to mainland France, but neither played a major part in the hostilities. Then, on 23 June 1940, one day after France signed the armistice with Germany, both companies were transferred to North Africa and disbanded in August.

These men formed the core of the 1st Régiment de Chasseurs Parachutistes (1st RCP) and the ‘Shock Battalion’ (Bataillon de Choc), established in 1943. The 1st RCP was trained and integrated into the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division, suffering heavy losses in eastern France during the autumn of 1944. Meanwhile, the Shock Battalion parachuted into southern France in August 1944, serving as the pathfinder force for the Allied Airborne Task Force.

In England on 15 September 1940, the 1st Air Infantry Company — 1ère Compagnie d’Infanterie de l’Air — was officially formed under the Forces Aériennes Françaises Libres. Some of these men were posted to the Middle East whilst others remained in the UK for clandestine warfare training by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and became the first members of the Free French Forces’ Military Intelligence Service known as the Bureau Central des Renseignements et d’Action (BCRA).

On January 2nd 1942, the thirty Free French paratroopers of the 1st Coy who had been sent to the Middle East and now designated 1ère Compagnie de Chasseurs Parachutistes — arrived at RAF Kabrit beside the Suez Canal, where they were integrated into Major David Stirling’s Special Air Service as the Free French Squadron. This unit later expanded to form the 3rd and 4th Regiments of the SAS Brigade, playing a key role in creating diversions during the Normandy invasion and engaging in operations in central and eastern France, as well as in Holland and Belgium in 1944.

Achille Muller was born on 01 January 1925, in Forbach, a town on the Franco-German border. Still a teenager when the Germans took control of the Alsace-Moselle region, he was made a German citizen. In July 1942, close to adulthood and forced conscription into the German army, he fled to join General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces. His escape took several months, crossing five borders before reaching Gibraltar and then the United Kingdom. Once he arrived in England, he was placed under surveillance for 72 days by British intelligence, who believed he was a spy.

On 23 June 1943 he was accepted into the Free French Forces and volunteered to be a paratrooper and as a member of the 4th Air Infantry Battalion (4e BIA) undertook parachute training under the supervision of the 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade at Upper Largo in Scotland, earning the Polish parachutist badge number 3473. In April 1944, 4e BIA became the (French) 4th SAS Regiment and as a member of this unit he participated in Operations DINGSON, SPENSER and AMHERST.

After World War II, the decision was made to establish airborne divisions in France and North Africa, and to send an airborne brigade to Indochina. The 1st RCP played a key role in developing airborne units stationed in France and North Africa, while the SAS Battalions were integrated into the French Colonial Marine Corps and promptly deployed to Indochina.

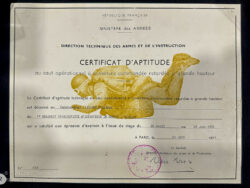

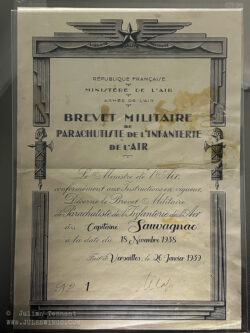

1946 – French Military Parachutist Brevet number 000 001

Officially designated the “Military Qualification for Parachutist” the current French military parachutist wing was instituted on 01 June 1946.

During the Second World War, several types of parachutist qualification badges were adopted by the French forces. British, French, American, and Polish – but without a standardised French pattern.

Beginning in 1945, efforts were made to unify these qualifications. Each certified parachutist was assigned a unique registration number recorded in an official register – a system that remains in use today.

The military parachutist badge that was adopted by the French incorporates the following symbolic meanings: “The wings lift you, the star guides you, the parachute supports you, and the laurels await you” with the oak leaves also representing the strength of the parachutist.

The first batch of wings was made by the Drago company, this badge features their ‘DRAGO 25 R. BERANGER PARIS III DEPOSE’ hallmark which was used in 1946. Since it’s inception there have been numerous manufacturers of the wing and collectors use the hallmarks and (if present) the registration numbers to date the wing.

Since its creation, the badge has been awarded to over 710,000 soldiers and its design has formed the basis for several wings used by former French colonies

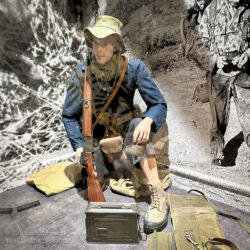

Zone 2. The Indochina War (1946–1954)

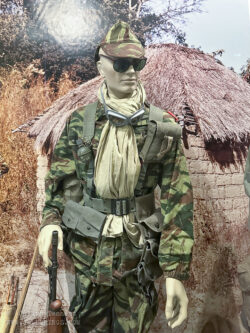

The next section reconstructs the operational environment in French Indochina, where airborne units were frequently used in vertical envelopment strategies and as a reaction force.

More than 200 airborne operations were carried out during the nine years of war in Indochina. Because the airborne troops constituted “the best infantry of the Expeditionary Corps,” they were used in every conceivable situation, from firefighters dropped onto Viet Minh infernos to units sent to the aid of other formations in difficulty. They were also sometimes misused due to the expeditionary corps’ understaffing and lack of air support. Yet it was in Indochina that the paratrooper spirit was born, characterized by its resourcefulness, audacity, endurance, and courage. Finally, it was in Indochina that air resupply took on considerable momentum and that the ability to deploy airborne artillery and engineering support units proved its full relevance and effectiveness.

In 1946, the SAS half-brigade and the paratrooper marching half-brigade, composed of elements of the 1st Shock Parachute Regiment and the 1st Parachute Chasseur Regiment (1er RCP), arrived in Indochina. In 1947, the first large-scale operations began, leading to the creation of new units: the Colonial Parachute Commando Half-Brigade and the Foreign Parachute Battalions. Drawn from the 25th Airborne Division (25e DAP) in mainland France, the parachute battalions were formed one after another, and the number of paratroopers involved increased, augmented by the Indochinese parachute companies.

In 1948, the 25th Airborne Division was dissolved in favour of an Airborne Troops Command, a detachment of which was stationed in Indochina to better manage the paratroopers deployed in the Far East. Some battalions, such as the 1st BEP and the 3rd BCCP, disappeared after fierce fighting. The first indigenous parachute battalions were created in 1951. In 1952, the 6th BPC was dropped on Tu Lê to rescue the last Thai garrisons retreating to the fortified camp of Na-San.

Operations Hirondelle and Camargue, conducted in 1953, were followed by Operation Castor in November 1953, the parachute drop to develop the French forward base at Điện Biên Phủ.

However, underestimating the Viet Minh’s capabilities and overconfidence in the effectiveness of the airlift led to the fall of the fortified camp on May 7, 1954. Seven parachute battalions were annihilated in the Battle of Điện Biên Phủ or disappeared in Viet Minh re-education camps. This defeat marked the end of the French presence in South East Asia.

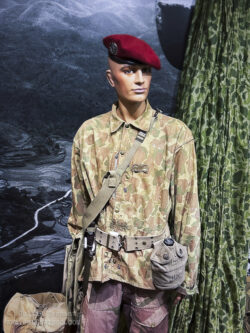

Zone 3. The Algerian War (1954–1962)

In 1956, following the withdrawal from Indochina, the French Army consolidated its airborne units into two parachute divisions: the 10th and 25th. These divisions were used as the primary strike reserves during the Algerian War (1954-1962) and the Algerian displays showcase the dual role of paratroopers in both high-intensity conflict and counterinsurgency. Unlike the sanitised historical displays of the Foreign Legion Museum, the Musée Mémorial des Parachutistes does not shy away from controversial operations such as the Battle of Algiers and the failed 1961 Putsch des généraux, offering critical insight into the politicization of elite military units during colonial disengagement.

On November 1, 1954, nicknamed “Red All Saints’ Day,” the 41st Parachute Half-Brigade, based in North Africa, was deployed to confront the first rebel groups and conduct pacification and peacekeeping operations. In 1955, the creation of two light airborne divisions was decided: the 25th Airborne Infantry Division, which became the 25th Parachute Division in 1956 by integrating the Colonial Parachute Brigade, and the 10th Parachute Division. The latter distinguished itself particularly in Operation Musketeer, conducted against Egypt on the Suez Canal. Unfortunately, political delays resulted in this operation being too late and too limited, leading to its condemnation by international opinion.

Meanwhile, in Algeria, the rebel groups received weapons and reinforcements from Morocco and Tunisia. In 1957, the Battle of the Frontiers began. Regiments of the 10th and 25th Parachute Divisions were used to intercept rebels in the mountainous areas. Distinguished by their responsiveness and endurance, the paratroopers performed admirably and achieved commendable results.

Also, in 1957, the 10th Parachute Division was sent to the Battle of Algiers and dealt a fatal blow to the terrorist networks. 1958 saw the adoption of the Challe Plan and the establishment of commando units to hunt down rebel groups. The paratroopers distinguished themselves during major operations: Etincelles (Sparks), Couronne (Crown), Jumelle (Twin), and Pierres Précieuses (Precious Stones) in the Oran, Algiers, and Kabylie regions. In 1960, when the rebellion was at its lowest point, the paratroopers were deployed to isolate the barricades, a mission they successfully completed.

In 1961, following the generals’ putsch in which paratroopers were involved, the three reserve divisions—the 11th Infantry Division, the 10th Parachute Division, and the 25th Parachute Division—were dissolved to form the 11th Light Intervention Division on May 1st. After the brief interlude at Bizerte in July 1961, the era of major interventions and a period of incessant fighting came to an end with Algeria’s independence in 1962.

In Algeria, the French paras confirmed their status as elite troops through both their remarkable conduct under fire and their innovative tactics. Alternating with equal effectiveness between peacekeeping missions, airborne encirclement operations, and pursuit in the mountains, they transformed the use of helicopters by combining them with close air support and flying command posts, making them both highly manoeuvrable and capable of conducting brutal assaults.

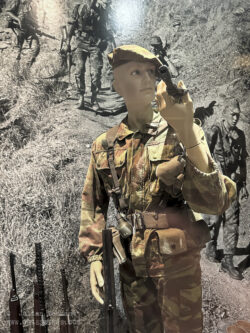

Zone 4. Post-Colonial Interventions

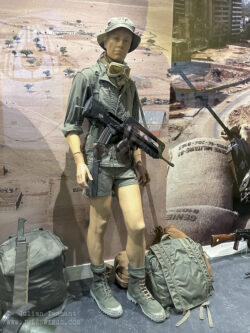

From Lebanon to the Balkans and the Sahel region in Africa, this section tracks the transformation of airborne forces into rapid deployment troops in service of international peacekeeping and French overseas operations (OPEX). These displays illustrate the evolution of the airborne regiments during this era through the modernization of equipment and doctrine.

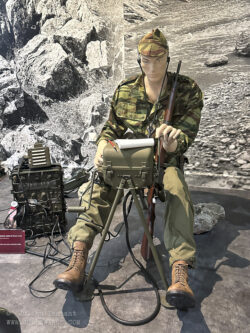

Zone 5. Contemporary Operations

This section addresses the current configuration of airborne forces, including their roles in Operation Barkhane in the Sahel, and global rapid reaction forces. It also underscores their integration with joint and multinational task forces under NATO and UN mandates.

The Temporary Exhibition Space

In addition to its permanent galleries, the Musée des Parachutistes features exhibitions tied to military anniversaries and current research.

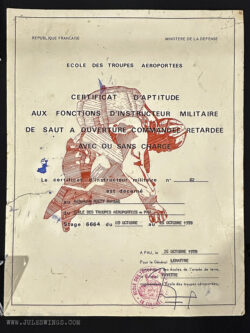

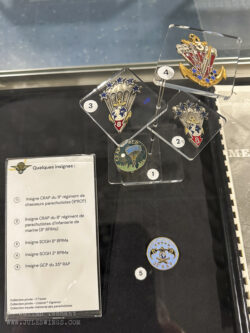

My visit coincided with the 60th anniversary of the first High Altitude Operational Parachute Course, so the exhibition, titled “High Altitude, High Precision: The Air Warriors” focus was on the Groupements de Commandos Parachutistes (GCP), Chuteurs Opérationnels (Chutops) and French High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) / Military Free-Fall (MFF) operations.

The exhibition presented a historical overview of the development of the Free-Fall capability within the French Army, equipment, selection, training and operational deployments of these specialised operators.

Right: An overview of the Chuteurs Opérationnels exhibition from the Musée des Parachutistes Instagram page

In Memoriam: The Crypt

At the center of the Musée des Parachutistes lies a crypt dedicated to the disbanded units and those who gave their lives in combat. Established alongside the Hall of Honor of the Airborne Troops School (ETAP), this crypt became the foundation around which the museum was built. It serves as a space of collective remembrance, offering both civilians and military personnel a place to honor the memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice.

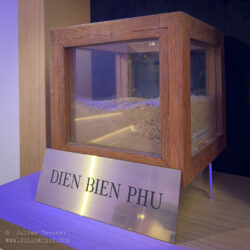

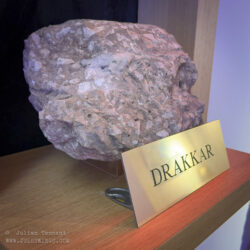

The crypt is divided into several spaces. On the left and right are the pennants of disbanded parachute units, in the center is part of the ‘prayer of the paratrooper’ engraved on marble. Above the flags are two symbolic relics; a box containing earth from Điện Biên Phủ and a stone from the Drakkar building in Beirut where 58 paratroopers of the 1st and 9th RCP perished in a suicide bomb attack on 23 October 1983. Finally, at the entrance to the crypt is the book of the dead, where the names of all the paratroopers who died in combat since the creation of the first French parachute units during the Second World War are inscribed.

Other Areas

Visitors complete their tour of the Musée des Parachutistes by passing through the gift shop area which in addition to a range of airborne related souvenirs also include some generic displays including an interesting map featuring para wings from countries around the world. Outside one can find a Panhard VPS Special Forces vehicle along with other vehicle and aircraft displays.

Reflections

The Musée Mémorial Parachutistes was one of the museums that I wanted to see for a long time and unlike the French Foreign Legion Museum which I visited during this same trip, it did not disappoint. This museum is filled with artifacts related to the periods represented and it does not ignore or gloss over the aspects of French military history that may be less than glorious. If you are a collector or somebody interested in France’s airborne history and post 1945 conflicts then the Musée des Parachutistes is a must visit. Highly recommended.

Visitor Information

Musée Mémorial des Parachutistes

Chemin d’ Astra

64140 Lons, Pau

France

Contact

Phone: +33 0559 404 919

Email: musee.parachutistes@gmail.com

Website: museedesparachutistes.com

Opening times

Monday – Thursday: 14:00 – 17:00 / Group visits can be booked in the mornings, 9 am to 12 noon. Closed Friday

The Musée Mémorial des Parachutistes is at the entrance to the École des Troupes Aéroportées (ETAP), on Chemin d’Astra, just off the main Bordeaux road (N134). Follow the arrows from the A64 exit “Pau-Centre”.