Dropping into the Cu Chi Tunnels

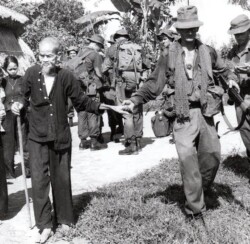

In January 1966, the 1st Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR), which had been attached to the US 173rd Airborne Brigade (Separate) after arriving in Vietnam the previous year, participated in Operation CRIMP. This was an operation involving over 8000 allied troops and is described in detail in Bob Breen’s book, First to Fight and in Blue Lanyard Red Banner by Lex McAulay, whose customised Australian Army lighter that he carried during the operation was featured in a previous post. CRIMP was the battalion’s first major foray into an area which has become synonymous with the famous Củ Chi Tunnels and the pioneering ‘tunnel rat’ work carried out by its sappers.

For 1RAR, the objective of this operation, which involved over allied 8000 troops, was a series of underground bunkers believed to be in the Ho Bo Woods area of Củ Chi district. Intelligence indicated that these bunkers housed the headquarters for the Communist committee that controlled all Viet Cong activity in the Capital Military District and a large complex of tunnels was subsequently uncovered by the battalion. For the first time, engineers of 3 Field Troop, Royal Australian Engineers (3 Fd Tp RAE), under the command of Captain Alexander (Sandy) MacGregor breached the network recovering large quantities of weapons, food, equipment and documents.

Sandy MacGregor recounts the experiences of the sappers from 3 Fd Tp as they entered the tunnels for the first time in his book, No Need for Heroes.

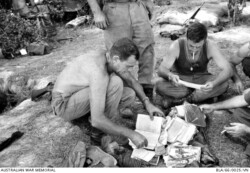

We had three tasks. The first was to investigate the tunnels as fully as possible to discover what they were being used for. The second was to try and map the tunnel system so that we could work out its extent, and if need be, dig down to a soldier who might be trapped. The third, once we discovered what a treasure trove the tunnels were, was to recover everything we could – weapons, equipment and paper – all of which was invaluable for the intelligence boys.

It was not an easy mission to accomplish as this was a departure from the American policy of sealing and destroying any tunnels found. Captain MacGregor had previously recognised the inadequacies of the American approach and had begun training his engineers to enter and clear tunnels. The 3 Fd Tp sappers had built a mock tunnel at their base, experimented and developed clearance techniques but they were still entering somewhat untested territory when they commenced the operation. The “Tunnel Rats” as they would come to known, had their work cut out for them. As soon as 1RAR hit the LZ they came under fire from snipers hidden in underground firing positions, trenches and tunnels. Bob Breen describes the situation in First to Fight,

There were snipers and small groups of Viet Cong everywhere – in and behind trees, popping up from spider holes and tunnel entrances at ground level, and scrambling away after firing quick bursts. The area was seeded with numerous booby traps. Diggers (Australian soldiers) noticed the ominous wires and saw shells and bunches of grenades dangling from trees and clumps of bamboo.

In an ambush on the first day of the operation, a Viet Cong firing position was discovered inside an anthill. When the sappers blew the anthill, a tunnel was discovered leading away from the position. Clearance teams from 3 Fd Tp began entering the network but breaching and securing the tunnels was no easy task.

We blew smoke into the tunnel and I divided the men into smaller sub-units of twos and threes and sent them off to investigate… Once we’d blown smoke, then tear gas, then fresh air down the tunnels, I sent a couple of men down to investigate. The entrance was so narrow it was hard to imagine it was intended for people at all. There was a straight drop then it doubled back up, like the U-bend under a sink. The tunnel turned again to go along under the surface and became a little wider, but there still wasn’t room enough to turn around. It was terrifying down there, armed only with a bayonet to probe for booby traps and a pistol to defend yourself.

Once you’d negotiated the tight entrance and the U-bend, you had to crawl along tiny passages, rubbing your shoulders on each side of the tunnel, on all fours, with no way of turning around if you got into trouble. Often, you’d find larger ‘rooms’, sections of tunnel that were big enough to crouch or kneel in, but you weren’t to know that when you first set out. The further the men went, the more complex the tunnel system was revealed to be. There were drops, twists and turns, corners around which the whole North Vietnamese Army could be waiting, for all they knew. The men burrowed away, ever further, ever deeper, until they discovered a hidden danger in the operation. Some of them began passing out in the tunnels due to lack of air. But, despite the fact that there was no room to turn they were all dragged back to the surface, usually after we’d blasted more fresh air down to them.

Unfortunately, one of the sappers, Corporal Bob Bowtell, succumbed to the lack of air in one of the antechambers and had died of asphyxiation by the time his body could be brought back to the surface. The operation took its toll on many of the sappers as George Wilson recalls in Gary McKay’s book, Bullets, Beans & Bandages,

Those long periods spent underground, often in total darkness, where at times the only ‘light’ was the luminous face of your watch, were my most vivid memories of Viet Nam… Our troop casualty rate was particularly high on that operation with only 12 out of 35 men remaining until the end… of the operation.

During the six days that 3 Fd Tp spent on Operation CRIMP, the sappers had investigated tunnels for 700m in one direction and another 500m across that line, recovering truckloads of documents and equipment, including photographs of the Viet Cong’s foreign advisors. On the final day of the operation, the sappers found a trapdoor which led to a third level in the system, but before they could investigate it further the Americans decided to end the operation and pull out. The tunnels that had been discovered were lined with explosives and tear gas crystals in an attempt to either destroy or make them uninhabitable. Later, long after the end of the war Sandy MacGregor finally learned what lay beyond that final trapdoor. It led to the military headquarters of the Viet Cong’s Southern Command.

They had been that close.

However, Operation CRIMP had uncovered a massive amount of equipment and intelligence information and as a result, American units throughout Vietnam received orders to clear tunnels before destroying them. The tunnel system breached by 3 Fd Tp was later discovered to consist of over 200 kilometers of tunnels in multiple levels, and included living, working and storage areas, forming part of the much larger Củ Chi tunnel complex. For his contribution, Sandy MacGregor was awarded the Military Cross by the Australian government and the Bronze Star by the Americans. He recounts his experiences developing the ‘Tunnel Rats’ concept and service in Vietnam in an interview that was recorded for the Life on the Line podcast series, which is worth listening to.

The Cu Chi Tunnels ‘Tourist Park’

The district of Củ Chi lies approximately 60 kilometers northwest of Saigon bordering an area known as the Iron Triangle, the heartland of the Viet Cong guerrillas operating in the region. The tunnel system took advantage of the hard, red, soil which was suitable for digging and did not become waterlogged during the monsoon season. It was first developed by the Viet Minh in their fight against the French and in 1947 only 47 kilometers of tunnels existed, but with the formation of the Viet Cong the system expanded. By the end of 1963 it was estimated that around 400km of arterial tunnels, trenches, connecting tunnels and bunkers existed in an area that covered 300 square kilometers. The Củ Chi Tunnel complex was big enough to conceal an entire regiment, some estimates put the figure at 5000 troops, enroute to its area of operations and proved to be an ongoing problem for the allied forces. Later, they were used as a staging area for the attack on Saigon during the 1968 Tet offensive and their utility was only somewhat restricted after a heavy bombing campaign by B-52’s in 1970.

During the course of the war it is estimated that at least 45,000 Vietnamese died defending the tunnels and after 1975, the Vietnamese government preserved sections of the tunnels and included them in a network of war memorial parks around the country. Today, visiting the Củ Chi tunnels are rated as one of the top five tourist destination activities in Vietnam, with some estimates placing the number of visitors as high as 1000 tourists per day.

There are two different tunnel display sites, Bến Đình and Bến Dược. The tunnels at Bến Dược are smaller attracting fewer visitors than the Bến Đình site which is closer to Ho Chi Minh City and is more popular with the multitude of tour groups offering the Củ Chi ‘experience’. Both tunnel sites offer a somewhat sanitised experience, allowing visitors to crawl around a ‘tourist friendly’ modified section of tunnel, check out displays depicting life for the occupants, boobytraps, weapons, equipment and be subjected to the usual pro-communist version of events. Personally, I think that the visitor parks are somewhat over-rated in terms of education or real historical value, but for a visitor with an interest in the military history of Vietnam they are worth visiting, just to check them out.

It is quite easy to reach the tunnels and there are lots of half-day or full day tours that include the Củ Chi Tunnels on their itineraries. Trip Advisor list several on their website which will give you an idea of what you can expect, however I think that it is best to visit them independently instead of an organised group tour. This can be done by bus or private taxi/driver, which is easily arranged and allows more flexibility with stops and timings.

.

The Cao Đài Holy See

Some of the organised full-day tours include a visit to the Cao Đài Holy See at Tây Ninh, approximately 96km northwest of HCMC as part of their package tour. Visiting this site is actually the main reason why I have made return visits to the tunnels at Củ Chi as its proximity makes for a good day trip and is worthy of consideration if you are organising your own visit.

The Cao Đài is a Vietnamese religious sect that was founded by a French colonial bureaucrat named Ngô Văn Chiêu and based on a series of messages he received during seances in the early 1920’s. Its doctrine is a fusion of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity and occultism which deified an unusual mix of figures including Joan of Arc, Victor Hugo and Sun Yat Sen. Officially recognised as a religion in 1926, it adopted a clerical organisation structure similar to Roman Catholicism, established its headquarters at Tây Ninh.

In the years following its establishment, the Cao Đài became increasingly active in politics and at its peak, during the French period, had a militia of around 20,000 troops under its command. The French Indochina wars form a large part of my interest in Vietnam and the sect was a major player in the south during the French era.

In 1933, the Cao Đài commenced construction of its main cathedral, the Holy See, which is described in Graham Greene’s book, The Quiet American as “a Walt Disney fantasia of the East, dragons and snakes in technicolour.”

Completed in 1955, the temple is a rococo extravaganza that mixes the architectural idiosyncrasies of a French church, Chinese pagoda, Madam Tussaud’s and the Tiger Balm Gardens in Hong Kong. Prayer services are held four times per day, when uniformed priests and laity enter the building to perform their rituals. Visitors are free to enter the balcony section of the temple during these prayers and it is a very colourful spectacle to watch the priests and dignitaries carry out their observances. The best time to visit is just before the midday prayers (held every day except during Tet) and then head on to the tunnels as the second stage of a full day trip.

.

Related items from the Juleswings Collection

One Comment

Comments are closed.